The piste map as record of the resortified alpine landscape

From Roman times until the early 1800s, the European Alps were shrouded in mystery – an unexplored, ‘uncharted wilderness at the heart of the world’s most crowded continent.’ The Alpine region represented a prison-like landscape, a place where outlaws were banished or individuals escaped to live separately from mainstream society and so became the setting for a multitude of horror stories. Rumours of ice witches living in the peaks, an entire alpine alien race and dragons who lurked in the rocky outcrops were widely believed.

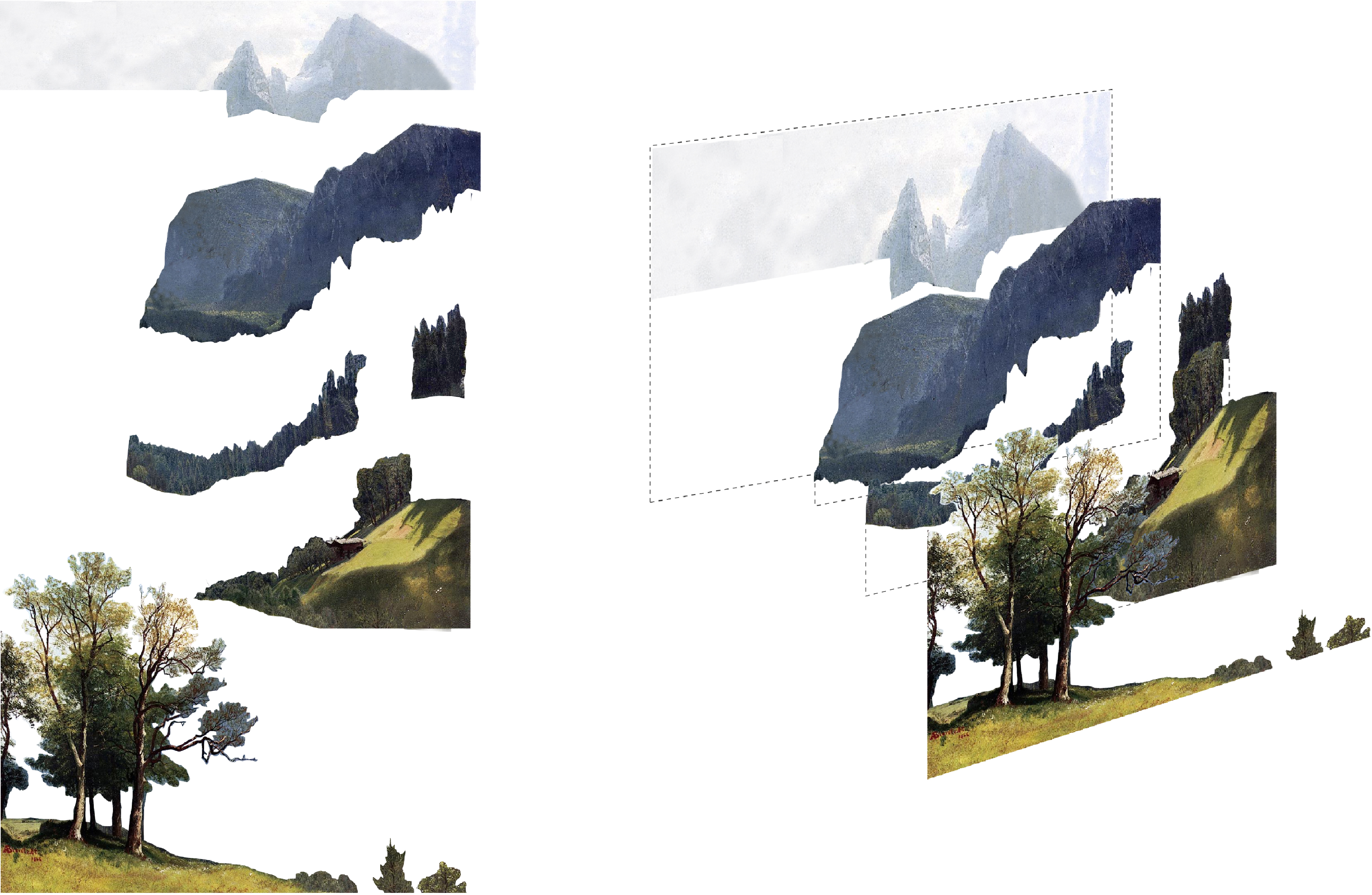

Artists such as Albert Bierstadt, J.M.W Turner and August Wilhelm Leu in particular, painted numerous scenes in the French, Austrian and Swiss Alps. Their paintings employ a key principle of romantic landscape composition; an abundance of layers or coulisses which form defined slices of ground each with their own characteristics, from the foreground to the background. The scenes are painted from a low perspective looking up to the peaks in the distance - from an accessible landscape, a bright flat meadow or pasture, looking up to the formidable peaks, the angle and composition portraying a sense of wonder for the inaccessible high altitude regions.

![caption]()

![]()

The resortification of the landscape refers to the transformation of the alpine landscape from a sparsely populated, largely inaccessible wilderness to a well-connected network of ski resorts and tourism related infrastructure. To resortify is to take command over the alpine landscape – to add a modern coulisse to the scenery, in the form of man-made augmentations and apparatus which attempt to tame the Alps‘ natural phenomena. In some ways resortification represents the inevitable outcome of the longing for the alpine landscape which developed in the late 1800s. As Marco Armiero wrote on the origins of the ski tourism industry, ‘romantic appreciation and modernization of nature were two sides of the same coin.’ It was this contradiction between a desire to experience the pristine landscape and the human interventions that skiers depended on to enjoy it, that led to the construction of railways, roads, hotels and eventually, in the late 1920s just in time for the first Winter Olympics in 1924, the invention of the ski lift.

![]()

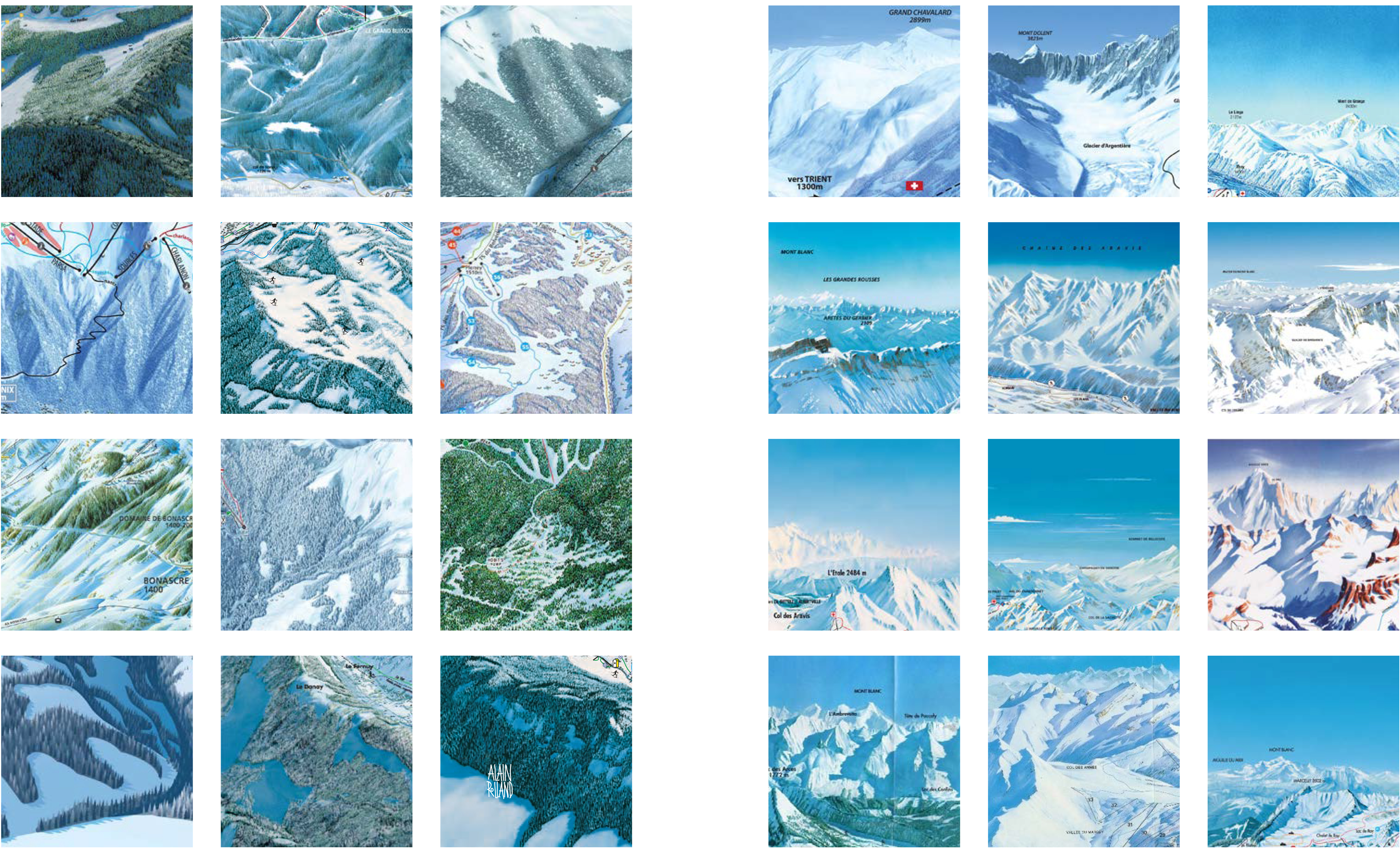

Perhaps the piste map is the modern equivalent of the Romantic alpine landscape painting, painted by specialist artists, commissioned by resorts to distribute to tourists. In some ways they are detailed geographical maps, showing each ski run, chair lift and resort amenity along with a detailed key. However, compared to a topographic map drawn accurately in plan view, it could be said that these maps are much more romantic in their nature.

Compositionally, the piste map bears striking similarities to Romantic alpine landscape paintings with clearly defined coulisses, transitioning from a familiar foreground to the distant backgroun peak-scape. The piste map is painted in some form of skewed elevation view, from the viewpoint of a particular resort and often represents an impossible landscape.

![]()

left: foreground depictions of buildings on French piste maps.

right: mid-ground depictions of the annotated ‘resortified’ landscape on French piste maps.

![]() left: mid-ground depictions of pine forests on French piste maps.

left: mid-ground depictions of pine forests on French piste maps.

right: background depictions of distant peaks on French piste maps.

From Roman times until the early 1800s, the European Alps were shrouded in mystery – an unexplored, ‘uncharted wilderness at the heart of the world’s most crowded continent.’ The Alpine region represented a prison-like landscape, a place where outlaws were banished or individuals escaped to live separately from mainstream society and so became the setting for a multitude of horror stories. Rumours of ice witches living in the peaks, an entire alpine alien race and dragons who lurked in the rocky outcrops were widely believed.

Artists such as Albert Bierstadt, J.M.W Turner and August Wilhelm Leu in particular, painted numerous scenes in the French, Austrian and Swiss Alps. Their paintings employ a key principle of romantic landscape composition; an abundance of layers or coulisses which form defined slices of ground each with their own characteristics, from the foreground to the background. The scenes are painted from a low perspective looking up to the peaks in the distance - from an accessible landscape, a bright flat meadow or pasture, looking up to the formidable peaks, the angle and composition portraying a sense of wonder for the inaccessible high altitude regions.

Fig.1 Bierstadt, Albert. “A Tyrolean Landscape.” 1858

Fig.2 Diagram demonstrating the ‘coulisses’ in Bierstadt’s painting, Ness Lafoy

The resortification of the landscape refers to the transformation of the alpine landscape from a sparsely populated, largely inaccessible wilderness to a well-connected network of ski resorts and tourism related infrastructure. To resortify is to take command over the alpine landscape – to add a modern coulisse to the scenery, in the form of man-made augmentations and apparatus which attempt to tame the Alps‘ natural phenomena. In some ways resortification represents the inevitable outcome of the longing for the alpine landscape which developed in the late 1800s. As Marco Armiero wrote on the origins of the ski tourism industry, ‘romantic appreciation and modernization of nature were two sides of the same coin.’ It was this contradiction between a desire to experience the pristine landscape and the human interventions that skiers depended on to enjoy it, that led to the construction of railways, roads, hotels and eventually, in the late 1920s just in time for the first Winter Olympics in 1924, the invention of the ski lift.

Fig.3 Le Grand Bornand piste map, 2002, Alain Rolland

Perhaps the piste map is the modern equivalent of the Romantic alpine landscape painting, painted by specialist artists, commissioned by resorts to distribute to tourists. In some ways they are detailed geographical maps, showing each ski run, chair lift and resort amenity along with a detailed key. However, compared to a topographic map drawn accurately in plan view, it could be said that these maps are much more romantic in their nature.

Compositionally, the piste map bears striking similarities to Romantic alpine landscape paintings with clearly defined coulisses, transitioning from a familiar foreground to the distant backgroun peak-scape. The piste map is painted in some form of skewed elevation view, from the viewpoint of a particular resort and often represents an impossible landscape.

left: foreground depictions of buildings on French piste maps.

right: mid-ground depictions of the annotated ‘resortified’ landscape on French piste maps.

left: mid-ground depictions of pine forests on French piste maps.

left: mid-ground depictions of pine forests on French piste maps.right: background depictions of distant peaks on French piste maps.

The drawings’ foregrounds always depict the

resort town, often as clusters of small farmhouse shaped symbols, on flat land.

The mid-ground layer, rises up behind the resort and presents the resortified

mountain-side, disected with the green, blue, red and black lines of ski runs

and chair lifts. Trees are removed entirely from this layer and the

delineations placed on a smooth, white backdrop of the terrain for clarity,

when in reality crevasses, clumps of pine trees and terrain variations would

obscure much of this from view if painted accurately. Artists paint the pistes

as clear cut out channels in a forest cloaked mountain-side representing a

clear diagram of deforestation patterns.

If the distracting layer of symbols and delineation were

removed from this type of map, we would be left with a painting which depicts the current state of

the alpine landscape, one which could be more clearly compared to its historic

counterparts. The maps often depict areas of dense forest which morph into

dramatic depictions of high alpine peaks in the distance which, much like the

mist cloaked, unreachable backdrops of Romantic alpine landscapes, hint at an

untouched wilderness just out of reach, beyond the conquered landscape of the resort. These forests frame the resortified slopes,

placing them in a psudo-wild context, giving the impression that this is a

small patch of tamed landscape in an infinite wilderness when often, in

reality, another resort lies on the opposite face of the mountain, in the

mirror image of this map, obscured by the curated viewpoint chosen by the

artist.

Excerpt from A Brief History of Alpine Resortification, Ness Lafoy, 2016

Excerpt from A Brief History of Alpine Resortification, Ness Lafoy, 2016